Brutalism: The Word Itself and What We Mean When We Say It

Posted: 20 November 2011 Filed under: Architecture, Brutalism, Events, Lectures 10 CommentsRecord of a Pecha Kucha-style presentation at Architecture + (Kent State), Friday November 18th, 2011

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The word “Brutalism” has lost its meaning. At present, it equates to: large buildings, sometimes of concrete, constructed sometime between World War II and the end of the 1970s. The sheer number of projects this describes is staggering, and many of the architects responsible for them in fact despised the term. We need to relearn the story of this pervasive locution.

Once upon a time, Brutalism referred only to “The New Brutalism,” a snide phrase coined by Alison and Peter Smithson to describe their unbuilt project for a townhouse in the SoHo neighborhood of London. For the Smithsons, “New Brutalism” was initially interchangeable with what they called “the warehouse aesthetic,” which sought to capture the raw quality of materials. As Peter Smithson pointed out in a late interview:

“Brutalism is not concerned with the material as such but rather the quality of the material, that is with the question: what can it do? And by analogy: there is a way of handling gold in Brutalist manner and it does not mean rough and cheap, it means: what is its raw quality?” [Peter Smithson: Conversations with Students, Princeton Architectural Press, 2004]

This raw quality, the treatment of materials “as found,” came to define the aesthetic proclivities of the group seen here, composed of the Smithsons, photographer Nigel Henderson, and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi. Eventually this group formed a part of The Independent Group, which is credited with launching Pop Art. For them, Brutalism was not a style but something else, hence:

“Brutalism tries to face up to a mass-production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work. Up to now Brutalism has been discussed stylistically, whereas its essence is ethical.” [Alison & Peter Smithson, “The New Brutalism,” Architectural Design (April 1957)]

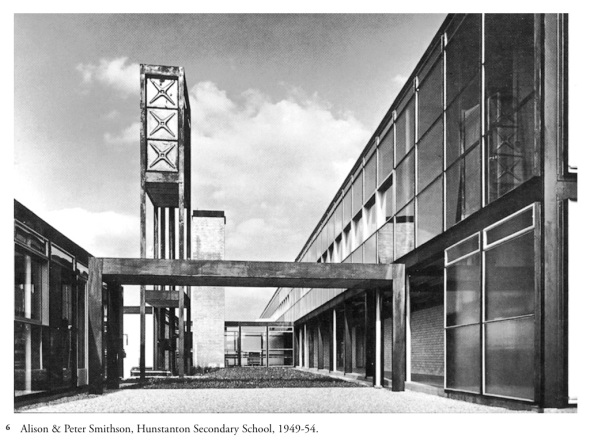

Immediately recognized as radical and transformative, “The New Brutalism,” was the subject of much debate. In fact, a series of think pieces had appeared in journals before the Smithsons managed to complete their first building, the Hunstanton Secondary School seen here.

One of brutalism’s strongest early supporters was historian and critic Reyner Banham. In 1955 he published an essay summarizing the defining characteristics of this new style as follows:

“1, Formal legibility of plan; 2, clear exhibition of structure, and 3, valuation of materials for their inherent qualities ‘as found.’”

Banham found this simple list inadequate, so he added:

“In the last resort what characterizes the New Brutalism in architecture […] is precisely its brutality, its je-m’en-foutisme, its bloody-mindedness.” [Banham, “The New Brutalism,” Architectural Review (December 1955)]

Banham later published what he purported to be the definitive statement on The New Brutalism, comprising an international selection of buildings. His contention was that the interplay of ethics and aesthetics defined production and reception of brutalism.

The trouble is, Banham excluded most of the buildings we now regard as brutalist. No Paul Rudolph, no Marcel Breuer, no Boston City Hall, and only one early project by Louis Kahn. And for the record, the Smithsons shunned Banham’s book, accusing him of co-opting their ideas to serve his own agenda.

Surely, the binary put forward by Banham is much too blunt and exclusionary. In order to rethink the word brutalism itself, it may be useful to return to the dictionary. Let’s look at the definitions of the parts in question. I’ve made a few redactions for the sake of brevity:

“brutal”

- savagely violent: a brutal murder

- punishingly hard or uncomfortable: the brutal winter wind

- without any attempt to disguise unpleasantness: the brutal honesty of his observations

“-ism”

- denoting an action or its result: baptism

- denoting a state or quality: barbarism

- denoting a system, principle or ideological movement: feminism

- denoting a basis for prejudice or discrimination: racism

- denoting a peculiarity in language: colloquialism

- denoting a pathological condition: alcoholism

[Oxford American Dictionary, 2007 Edition]

If we cut and paste a bit we might come up with something satisfactory:

“brutalism”: A state or quality of principled but pathological hardness or discomfort, without any attempt to disguise its unpleasantness.

A bit convoluted, but you get the point. Using this makeshift definition, the word itself might be reframed to describe a particular attitude about building, best described by Banham’s “bloody-mindedness.” Unlike the historically loaded word style, the idea of an attitude might effective at drawing together the diverse group of architectures to which we affix the word in question.

Universally recognizable by its severe, abstract geometries and the monolithic use of concrete, block and brick – this attitude called brutalism became a consensus approach to monumentalizing modern architecture.

If this story of Brutalism is indeed about consensus, our primary question should be: what made this uncompromising, imposing, and frankly quite impractical attitude so seductive?

The story of Paul Rudolph’s Art & Architecture building at Yale University might be instructive. Commissioned when Rudolph was appointed dean at the Yale School of Architecture, the completed building is overflowing with quotations and citations of the history of architecture.

Like Wright’s Larkin Administration Building, Rudolph wanted his work at Yale to have a sense of permanence, a built-in history, monumental enough to rival Roman ruins. In spite of his erudition, Rudolph’s building is most often remembered as the site of a mysterious arson.

The oft-cited myth is that a disgruntled architecture student, fed up with the building’s presence in his life, set fire to his desk in protest. True or not, this myth makes discussion of the building’s architectural merit or lack of merit extremely difficult. When we talk about Rudolph, we have to talk about the fire.

I’m tempted to cite Bernard Tschumi’s “Advertisements for Architecture,” in particular two sentiments expressed here, below the photographs:

On the left, “Architecture is defined by the actions it witnesses as much as by the enclosure of its walls.” And on the right, “Architecture only survives where it negates the form that society expects of it.” Through his actions, the arsonist responsible for Yale’s fire altered the narrative of Rudolph’s building and of brutalism in general, but might the story someday change?

While no mysterious event clouds our view of the Hunstanton School, the overwhelming personal narrative constructed by Alison + Peter Smithson certainly does. Known for talking big and building little, the Smithsons were never as successful as their books would have you believe.

Their largest project, Robin Hood Gardens council housing in London, is one of the worst failures of urban renewal during the brutalist moment. Its foundering hurt their reputations, and larger commissions never came their way. Unlike Rudolph, however, the Smithsons regained their stature by changing their attitude. Their work in the 1970s traced a shift away from the unhomely airs of brutalism toward a sophisticated engagement with Postmodernism, and a more open embrace of history.

The story of brutalism reminds us that once upon a time, there was disciplinary consensus. In retrospect, this consensus appears a peculiar convergence between ethics and aesthetics, during which truth in materials and the question of monumentality dominated the discipline no matter one’s ideological bent, a time when do-gooders and designers held certain goals in common. Successful or not, the results of this peculiar convergence are all around us, reminders that we could all use an attitude adjustment.

An excellent starting-point for making sense of the recent Brutalist Revival. (I remain convinced, btw, that we are in the age of Team Twenty-Ten, for reasons that combine demographic bubbling and successive father-killings within the discipline.) Definitely, the terminology needs to get pinned down a little bit; at the same time, I’d like to see it critiqued more. For one thing, the figure of the Brutalist architect that emerges has this old-school Randian masculinity to it: the principled, bloody-minded ascetic, willing to suffer (and make others suffer) hardness and discomfort for the Greater Goal. I wonder how accurate that is, particularly when you bring in people like Hertzberger who really thought (rightly or wrongly) that they were giving people the chance to impress themselves and their lives on the architecture. Comfort (and the small niceties of social etiquette) were at the center of projects that – if we *were* categorizing in terms of style – seem just as Brutalist as all the others.

Another way of putting it: if Brutalism was an attitude more than a style, how do we figure out who shared that attitude? (I think the unanimous disciplinary consensus you suggest is a little implausible.) If it was an attitude that included, as one of its features, the embrace of certain stylistic tics, we’re back at square one of defining what those were, in the face of the term being used to describe countless things that look nothing like each other…

The attitude I’m trying to describe is about truth/honesty in materials, and an interest in the question of monumentality (not stating pro or con). I agree with you that the notion of unanimity within the discipline is implausible, but I’m taking some liberties to construct a clean narrative like the Smithsons did in their writing. If you look at their work over the course of twenty or so years (1950-1970), it’s inconsistent as hell. But through their narrative agility they were able to tell their story several different ways in different books. My favorite is of their books is Without Rhetoric, which comes closest to outlining an attitudinal definition of brutalism, citing everything from Mies to Kahn all the way to vernacular building.

I admit the definition I constructed in the middle is a bit heavy handed, and I hope this doesn’t read like I’m in favor of some Roarkian archetype. The point I was trying to make was about the Smithsons changing their attitude and rethinking their narrative. I think it’s about storytelling as much as it’s about brutalism.

And Team Twenty Ten? Count me in.

“not stating pro or con” – – I like this. Defining it more in the questions to be asked or the issues on which one had to take a stance – – to carry on Modernism in the 50s and 60s required you to puzzle out the paired questions of monumentality and history, and maybe also figure out what architecture’s relationship was to the ginormous new super-institutions of the postwar period… it gets a bit circular and hazy as a definition, to the point where it’s just refusing the dilemma, but I can sort of imagine a discussion around “The Brutalist Period” as opposed to “Brutalism,” if that makes sense.

A definition based on questions also, I think, makes it easier to stretch the category and consider people “changing their attitude and rethinking their narrative.” This is all pre-coffee though.

A huge point of interest for me is the whole “why now” thing with the revival, your blog. It can’t just be generational (although I insist that’s part of it) – Flickr, for example, is rife with people a good bit older than us, oohing and aahing and exchanging long words of appreciation concerning the work of figures who would have been scarily unfashionable a few years ago.

New Abstraction-ists is what we came up with for Post-Post Modernism (stupid in the first place we all living in the ‘modern age’). Like TTT though.

As an older student (late forties) and having grown up with the utopian Brutalist style my only comment is the social engineering of local councils, poor construction (my father was a site manager on these projects, all price work with little or no supervision) and poor maintenance are the reasons for most of the failures. Could they have worked in more enlightened time? Well the gentrification of the Barbican shows its about peoples adoption of buildings. Its not the building, but the attitudes of the people who reside there. Treat people like shit and expect a building to change their attitude? I think not. So i will always blame the Client (being local government) more than the Architects in this case.

Personally sick to death of narrative, context, i want things to work.

“Brutal” is derived from “beton brut”, French for “raw concrete”. But it would seem the Smithsons were having a bit of word fun with the term.

yep. Surprised this was not raised in the article

[…] included) off to Google for a definition. I found this site that seems to explain Brutalism well: https://criticundertheinfluence.wordpress.com/2011/11/20/brutalism-the-word-itself-and-what-we-mean-w… [Note from Pam, here is my story on Brutalist […]

The fifth definition of brutalism ought not be struck out. Colloquialism- as in the warehouses the Smithsons referenced and as in free of rhetoric, blunt.

Great work, thank you. In researching the architecture of my home town I was surprised by the ‘Brutalist’ term and you explained it brilliantly.

[…] La imagen del post es la Hunstanton School de los Smithson, Norfolk, de 1949–54. Más información en https://criticundertheinfluence.wordpress.com/2011/11/20/brutalism-the-word-itself-and-what-we-mean-… […]