Handicapping the Pritzker Prize, 2013 Edition

Posted: 17 February 2013 Filed under: Architecture | Tags: aires mateus, alberto campo baeza, Architecture, David Adjaye, david chipperfield, diller scofidio renfro, giancarlo mazzanti, holl, kengo kuma, o, Pritzker Prize, sean godsell, sou fujimoto, studio mumbai, un studio 8 CommentsAfter last year’s successful pick of dark horse Wang Shu (5:1 odds), a continuation of my Pritzker Prize series seems in order. No promises for a similar success this year, but I think that Shu might be a bellwether for changes in the ambitions of the prize. Perhaps the jury as currently composed will be able to set aside the Eurocentrism of decades past and see to it that a more broad array of architects are on the list of nominees.

**************************************************************************

5:1 – Kengo Kuma (Japanese, b. 1954)

The reason Kuma’s work is so appealing is hard to put your finger on, but I think it’s mostly his experimentation with materials. In the past few years a number of his completed projects have made the rounds of architecture publications, and they have all been wonderfully inventive and quite beautiful. Kuma also strives to make an environmentally conscious architecture that is also aesthetically robust.

5:1 – David Adjaye (British, b. Tanzania 1966)

Adjaye’s profile has never been larger, with the National Museum of African-American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. under construction, and with his studio’s incredible churning of publications. It would be a great boon for the Pritzker to be awarded to an architect of African descent, and Adjaye is the strongest candidate in my opinion.

8:1 – Giancarlo Mazzanti (Colombian, b. 1963)

The Pritzker hasn’t typically rewarded architects whose work has much of a social agenda, but Mazzanti is an example of an architect whose work is aesthetically daring and socially active. South American architects are extremely underrepresented in the Pritzker canon, and Mazzanti would be a great choice to start changing that.

8:1 – Liz Diller (American, b. Poland, 1954) and Ricardo Scofidio (American, b. 1935) of Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Lincoln Center is done. The Hirshhorn Bubble continues to incite controversy. The High Line is ongoing and continues to accrue much acclaim. The Broad and Berkeley Art Museums are under construction, as are several large academic buildings. Now’s the time for DS+R in my opinion.

10:1 – David Chipperfield (British, b. 1953)

In recent years, Chipperfield has built up a significant portfolio of slick minimalist public buildings around the world and in Great Britain, and he just curated the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale which bade well for Kazuyo Sejima in 2010. That being said, Chipperfield is a well-known British architect at the height of his career, which doesn’t align with the stated ambition to award those whose careers are on the upswing.

10:1 – Alberto Campo Baeza (Spanish, b. 1946)

The Pritzker has recently rewarded architects whose work has maintained consistency and quality over time, and Campo Baeza is a perfect example. Both his small houses and large cultural buildings use the same minimal vocabulary and impeccable detailing. The clarity and reductiveness of his work is seductive but leaves many people cold.

10:1 – Sou Fujimoto (Japanese, b. 1971)

By far the youngest candidate on my list, Fujimoto has been on a meteoric rise the past two or three years, raising his international profile by exhibiting at the Venice Biennale, and promoting his works worldwide through photographs by Iwan Baan and others. It has just been announced that he will be building this year’s Serpentine Pavilion in London, and the vast majority of architects invited to do so were or became Pritzker winners. He has a strong chance.

12:1 – Manuel & Francisco Aires Mateus (Portuguese, b. 1963 & 1964)

Rising fast, the brothers Aires Mateus are nominated for the Mies van der Rohe prize this year, and exhibited an impressive work at the Venice Biennale. Good candidates.

15:1 – Steven Holl (American, b. 1947)

I think Holl has become a long shot. If they were going to give it to him, they would have done so by now. As a world-famous American architect in his 60s, he doesn’t fit the bill for the new Pritzker.

15:1 – Sean Godsell (Australian, b. 1960)

His rather amazing Design Hub at RMIT opened this year, after almost two decades of residential work that has mined the potentials of architectural skins and surfaces. I think he would be a great choice. Boxes have never looked as good.

20:1 – Ben Van Berkel (Dutch, b. 1957) and Caroline Bos (Dutch, b. 1959) of UN Studio

Though UN Studio seems to be quiet lately, its collaborative partners are still strong candidates because of the well-considered balance of theorizing and building that makes up their practice. The Mercedes Benz Museum they completed a few years ago remains one of my favorite buildings of the last decade, and seems to have been overlooked at the tail end of our worldwide obsession with iconic architecture.

25:1 – Bijoy Jain (Indian, b. 1965) of Studio Mumbai

Studio Mumbai has increased its international profile in the past couple of years, exhibiting at the Venice Biennale and the Victoria & Albert in London, and recently publishing a monograph in El Croquis. Their work is intensely regional and specific, but its lessons for the West about integration with craftspeople and constructors are invaluable.

**************************************************************************

I have admitted that it is unlikely Peter Eisenman, Toyo Ito, Daniel Libeskind or Wolf Prix will ever win the Pritzker, so I’ve dropped them from my list. I also think that in the interest of diversification, it’s not likely that a younger North American architect will win this year either. That disqualifies Michael Maltzan, Brad Cloepfil, John & Patricia Patkau, and several others who would have been strong contenders ten or fifteen years ago.

Book Review: Diagramatically, Urban Infill Volume 5 by Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative

Posted: 14 February 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentThat diagrams are increasingly important representational tools for the practice of urban design seems indisputable, but it makes a provocative “Urban Infill” topic for precisely that reason. Modes and methods of representation are too often taken for granted in design practice, and anything more than shallow consideration paid to them is worthy of recognition. That being said, this particular representational device, the diagram, is exceedingly hard to pin down and its definitions are far from obvious. Avoiding the temptation to hazard any such definitions for the most part, this volume presents 17 perspectives from academics and practitioners alike. While a bit over-taxonomized (are six separate sections really necessary?), these essays illustrate a diversity of opinions, from the earnest to the instrumental.

On the side of the earnest are several submissions concerning the social agency of diagrams, directly problematizing their ability to communicate design ideas to the broad constituencies with whom urban designers interact. While some of this group contain a bit too much altruism for my taste, others illuminate the versatility and power of even the most straightforward graphic representations. Of more interest to this reviewer are a few explorations of the often instrumental quality of diagrams. The work of many in this volume aims to reveal the diagram as not just an altruistic communicative tool but one whose purported transparency can in fact conceal underlying preconceptions and ideologies. Precious few, however, propose strategies for designers to overcome such instrumentalization.

All told, this volume sketches a broad outline of the practical, social and theoretical implications of diagrammatic drawing, and for that, CUDC should be commended. “Diagrammatically” will no doubt prove an invaluable resource for students of urban design – both in Cleveland and nationwide – for years to come.

Classic Book Review: Reyner Banham’s “A Concrete Atlantis”

Posted: 25 June 2012 Filed under: American Culture, Architecture, Book Reviews | Tags: A Concrete Atlantis, Architecture, Book Review, Book Reviews, Industrial Buildings, MIT Press, reyner banham Leave a commentThis is an extremely remarkable little book that has reoriented my perception of the humble (and not so humble) industrial buildings that surround me. Conversational and highly personal, it explores an overlooked influence on early Modernism, a set of photographs published by Walter Gropius in 1913. Banham traces the typological developments that led to the distillation of two American building types Gropius selected – concrete grain elevators and “daylight” factories – and points out their unbelievably rapid obsolescence. These types lived on in the factory aesthetic of European Modernism, and Banham’s third chapter outlines how.

Part of what makes this book remarkable is Banham’s hybrid memoir/historical formatting, which exposes the methodology of his research. He prioritized close reading not in abstract, academic terms, but first hand visitation of buildings, a rite of passage that builds credibility for any historian of our built heritage, and is a phase of research I often find myself forgoing in the internet age. Unfortunately, many of the buildings Banham visited have since been demolished, and in exploring their history he illustrates how invaluable our industrial heritage can be and the low esteem in which we hold its monuments. It’s also unfortunate that this book, published over 25 years ago, hasn’t caused a change in perception with regard to these irreplaceable buildings. They continue to decay and be demolished at an alarming rate. They might be gone before we know it.

The MIT Press, April 1989

Book Review: The Interface: IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design, 1945-1976

Posted: 8 March 2012 Filed under: Architecture, Book Reviews, Exhibitions, History, Postmodernism, Product Design, Technology | Tags: Charles Eames, Eliot Noyes, IBM, John Harwood, Quadrant Books, The Interface, University of Minnesota Press 1 CommentThis book is a fleet-footed and exhaustive survey of the role of Eliot Noyes, Charles Eames and many others in the IBM Design Program. Though ostensibly focused on architecture, author John Harwood effectively integrates industrial, graphics, and exhibition design through a series of chapters that explore their roles in the development of both the computer and the multinational corporation. Harwood argues that these designers, Noyes in particular, were essential in assessing the importance of interfaces on both fronts. In outlining the division between “parlor and coal cellar” in the design of computers, and naturalizing the increasingly prominent role of computers and other teletechnologies in daily life through exhibitions and architecture, the IBM Design Program transformed the role of design in both realms.

The strongest and most engrossing of Harwood’s chapters for me is his third, which deals with IBM’s architecture. Not only did Noyes’ firm complete a series of buildings for IBM on their own, Noyes hand selected the architects for most major commissions. The results, though typologically (and topologically) similar, speak to the diversity of thought on modern architecture during the mid to late 20th Century. For Harwood, what makes these buildings important is not just their aesthetic diversity, but the integration of their technological function with their organization. Many of these buildings were either inward-facing or entirely isolated, though their control on the surrounding environment belied this isolation. The further inward these buildings focused, the more command they embodied.

Harwood’s concluding observations have to contend with the recent trajectory of corporate design (1976-Present) and this presents some difficulty. Noyes, through his prominent role as design consultant, seems to have designed and managed his way out of the process, to have made his role redundant. Today’s corporate design culture is much different and more resistant to outside influence (for more see my recent article on Apple’s architectural patronage in CLOG: Apple).

Harwood sees methodological transformation in the research at hand, specifically progress toward the removal of aestheticization from histories of architecture and technology. The appearance of things can no longer be the only way of assessing their significance. The world that present-day historians have to contend with is dramatically different from that even a generation ago, and their methods must change in response. Harwood has provided an elegant model.

A Quadrant Book, University of Minnesota Press, 2011

Handicapping the Pritzker Prize, 2012 Edition

Posted: 25 February 2012 Filed under: Architecture 4 Comments

Time for my annual run-down of Pritzker Prize candidates. The announcement of this year’s winner should be coming in the next few weeks. I’ve included a broader array of architects this time in response to my overlooking of Souto de Moura last year.

**************************************************************************

3:1 – Steven Holl (American, b. 1947)

I’m sick of talking about reasons why Steven Holl should win the Pritzker. They’re presenting the prize in China this year, which is the site of many of Holl’s recent achievements. To overlook him once again would be a major snub.

5:1 – David Chipperfield (British, b. 1953)

In recent years, Chipperfield has built up a significant portfolio of slick minimalist public buildings around the world and in Great Britain, and he is curating the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale which bade well for Kazuyo Sejima in 2010. No projects in China with the exception of a museum renovation in Shanghai, which may hurt his chances this year. (Correction: Chipperfield has also completed the Liangzhu Culture Museum in Hangzhou, see comment below)

5:1 – Wang Shu (Chinese, b. 1963) of Amateur Architecture Studio

Among internationally recognized Chinese architects, Wang Shu is the prime candidate given his age and portfolio. Putting it that way is selling his firm’s work way short, however. Their material and formal experimentation at a diversity of scales is impressive to say the least. (I must acknowledge the role of Tenuous Resilience in my recognition of Wang Shu as a candidate)

7:1 – Liz Diller (American, b. Poland, 1954) and Ricardo Scofidio (American, b. 1935) of Diller Scofidio + Renfro

DS+R have completed their multi-phase renovation of Lincoln Center in Manhattan to much acclaim, and their firm is currently working on a number of major museums in the Western Hemisphere, along with the continuing work on the acclaimed High Line Park. I like their chances.

10:1 – Alberto Campo Baeza (Spanish, b. 1946)

The Pritzker has recently rewarded architects whose work has maintained consistency and quality over time, and Campo Baeza is a perfect example. Both his small houses and large cultural buildings use the same minimalist vocabulary and impeccable detailing. The clarity and reductiveness of his work is incredibly seductive but leaves some people cold.

12:1 – Giancarlo Mazzanti (Colombian, b. 1963)

The vast majority of Pritzker winners have been of European descent, and it seems high time the jury rewarded a South American architect of Mazzanti’s caliber. His work is regionally sensitive but internationally relevant, and the formal research of his recent buildings is balanced by a robust social agenda.

12:1 – Kengo Kuma (Japanese, b. 1954)

The reason Kuma’s work is so appealing is hard to put your finger on, but I think it’s mostly his experimentation with materials. If his V&A satellite in Dundee, Scotland turns out as wonderful as renderings make it appear, I think he will win soon.

15:1 – Ben Van Berkel (Dutch, b. 1957) of UN Studio

UN Studio seems to be weathering the recession just fine, working on projects in Singapore, Georgia, completing exhibition and pavilion designs in Europe and the Americas, and designing furniture. Despite being relatively quiet of late, Van Berkel is still a strong candidate.

15:1 – David Adjaye (British, b. Tanzania 1966)

Adjaye’s profile has never been higher, given that he has just broken ground for the National Museum of African-American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. After that project is completed, I expect Adjaye to win.

20:1 – Toyo Ito (Japanese, b. 1941)

The second oldest of my candidates and by far the most established, Ito is not a likely winner, but would certainly be deserving. Given that he now has a museum dedicated to his architecture, the jury will be increasingly unlikely to award him the prize.

20:1 – Craig Dykers (German-American, b. 1961) & Kjetil Traedel Thorsen (Norwegian, b. 1958) of Snøhetta

Despite their first building in North America being a “failure in a flyover state” in my own words, Dykers and Thorsen continue to grab commissions and garner critical praise. When the 9/11 Memorial and their addition to SFMoMA are completed, look for Snøhetta to be strong contenders.

25:1 – Brad Cloepfil (American, b. 1956) of Allied Works

Cloepfil has just completed his most critically-lauded building to date, the wood and concrete Clyfford Still Museum in Denver. I’m not sure what Allied Works has on the boards, but if they continue to produce work as beautiful as the Still, Cloepfil could win before we know it.

25:1 – Michael Maltzan (American, b. 1959)

Another strong American candidate, Maltzan has gained much attention in recent years for his work for the Skid Row Housing Trust and small projects in Los Angeles. If larger commissions continue to roll in, I think he should win the Pritzker in the near future.

30:1 – Valerio Olgiati (Swiss, b. 1958)

I might be playing favorites here, but Olgiati has put together one of the most mystifying oeuvres of any contemporary architect. His bold use of concrete and other materials, in concert with the way he deploys vernacular references and decoration all make him a good candidate if you ask me. But it’s likely too soon after Peter Zumthor to see another Swiss architect be awarded the prize.

30:1 – Preston Scott Cohen (American, b. 1961)

Have you seen his museum addition in Tel Aviv?! That project alone should be enough to make him a candidate, but isn’t enough to win him the prize. If PSC’s practice continues to grow and his commissions do too, look for him to be a potential Pritzker winner in a few years.

50:1 – Alejandro Aravena (Chilean, b. 1967) of Elemental

Aravena is probably too young to win this year, but like Mazzanti, his incredible formal inventiveness is balanced by the social agenda foregrounded by his social housing firm Elemental. He’ll become a likely candidate in the future.

50:1 – Bijoy Jain (Indian, b. 1965) of Studio Mumbai

Studio Mumbai has increased its international profile in the past couple of years, exhibiting at the Venice Biennale and the Victoria & Albert in London, and recently publishing a monograph in El Croquis. Their work is intensely regional and specific, but its lessons for the West about integration with craftspeople and constructors are invaluable. Look for Bijoy Jain to be a future candidate.

**************************************************************************

I have admitted that it is unlikely Peter Eisenman, Daniel Libeskind or Wolf Prix will ever win the Pritzker, so I’ve dropped them from my list. There is, however, one final candidate I’d like to mention, who I think is the ultimate dark horse:

100:1 – Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957) of Fake Design

Would they do it? Give the Pritzker to an artist (one who also makes quite wonderful buildings) in China just a year after his detention for dissent? Probably not, but it would be incredible if they did.

Local Wonder: Wolfe Center for the Arts, Bowling Green

Posted: 14 January 2012 Filed under: Architecture, Snohetta | Tags: Architecture, BGSU, Bowling Green, Ohio, Snohetta, Theatres, Wolfe Center for the Arts 2 CommentsWhen I first heard that Bowling Green State University had commissioned the internationally renowned architecture firm Snohetta to design their new performing arts building, I was cautiously optimistic. For their first building in North America, the Oslo-based office had taken a surprisingly small commission in a surprisingly backwater location. Best known for their elegant landform buildings for the Oslo Opera House and Bibliotheca Alexandrina, how well could their work translate to an unmemorable campus devoid of the drama of those sites? What would their response be to the soporific landscape of Northwest Ohio?

In gestural terms, the new Wolfe Center for the Arts at BGSU is a rousing success. Rising dramatically from a flat site, its metal panels and tilted geometry have introduced a completely new vocabulary to an otherwise banal group of campus buildings. A glazed facade terminates this rise, cantilevering over the entry and imposing itself on the adjacent parking lot.

The Wolfe Center lobby is light-filled and well appointed. It is dominated by a grand concrete stair/bleacher at its center, a clever element which effectively ties together the room’s two functions: campus lounge and posh reception area. This striking element will no doubt be used as both a place to study and a people-watching perch similar to the famous stair and balconies at Charles Garnier’s Paris Opera. The other dominant lobby element is a large skylight at the terminus of the stair. Its size and shape gave the space a pleasant atmosphere on the cloudless day of my visit. Early renderings show a series of these skylights, but it seems to this author that more would have caused the interior to be overlit and seem more sterile.

Equally dramatic is the skylight running the full length of the back-of-house hallway. Clad in dark gray CMU and charcoal stained wood paneling, this space, though less ambitious, is just as successful as its larger cousin. Both these spaces for movement overshadow the small theatre spaces at the building’s heart.

One can exit the building onto a small patio framed by offices for performing arts faculty, paved in a linear pattern that appears a vestige of value engineering. On this side, the Wolfe camouflages itself within a hill. This green slope will eventually be used for outdoor performances, but its sod was yet to establish itself at the time of my visit.

As successful as the overall building gesture is, a few confusing and inconsistent details almost sink it. A preponderance of small issues has added up to a big problem. The most egregious error involves a pair of sprinklerheads unceremoniously placed in the aforementioned lobby skylight atop plumbing (thankfully) painted to match the adjacent wall. Details like these are often symptomatic of a strained relationship between design and executive architects. Leaving construction administration in the hands of locals, global practices can sometimes lose control of important details to a building’s detriment. It seems likely this has happened to the Wolfe.

From a design standpoint, there are a few questionable moves as well. 1) On the building’s flanks, windows don’t occur often enough to become a pattern, and instead seem capitulations to programmatic circumstance. 2) Just inside the building’s prow lies a group of small classrooms that are fully isolated and surrounded by circulation, creating an island or a building-within-a-building. While this does create a observation spots on either side, it results in strange fish-tank-like spaces. 3) The selection of concrete masonry walls for some interior spaces is disappointing. It seems to lower the building to the level of its neighbors, and gives these spaces an unfortunately institutional atmosphere.

A central question for me is whether this commission even worthy of Snohetta. Commissioning an internationally recognized office for such a modest building meant it must have been a chore rather than a labor of love, and perhaps its shortcomings are the result of a lack of attention. But when Craig Dykers and co. are simultaneously working on the 9/11 Museum in Manhattan and an addition to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, who can blame them? While the Wolfe Center is far from perfect, here’s hoping more state universities take chances on ambitious architecture in the future. Perhaps the lesson here is for other campuses to work with younger, perhaps local outfits looking to establish themselves rather than an international crew whose reputation may not be tarnished by a failure in a flyover state.

Book Review: The Architectural Detail

Posted: 28 December 2011 Filed under: Architecture, Book Reviews | Tags: architectural detail, Architecture, Book Review, Edward R. Ford, Princeton Architectural Press, The Architectural Detail Leave a commentThe good detail is not the part from which the whole is generated, not the idea of the whole carried into the part, not the consistent application of a set of principles, not the paradigm for the totality of the building […] At its best it is an autonomous activity, and, at times, even subversive. (45-46)

The new book by Edward R. Ford, author of the weighty Details of Modern Architecture, sets out to answer the question, “What is a detail?” His answers are fragmentary at best, but their contradictory conclusions seem to support Ford’s argument better than a succinct, universal answer would, and the book itself seems to be constructed as an analog to said argument. The book is divided into seven chapters, presenting a series of different definitions of the architectural detail, and concluding with a chapter instead defining the activity of detailing. Defining a derivative rather than the root – or the means rather than the end – is a successful gambit for Ford, permitting his speculative conclusion rather than an encyclopedic one.

Ford begins by dismantling a number of widely held opinions about the function and form of details. An early chapter (‘There Are No Details’) battles the opinion that “To many modernists […] details are impossible, unnecessary, or undesirable.” In response, Ford outlines reasons why the way parts come together matters even when the architect may say it doesn’t. What is at issue in details for Ford is the negotiation of contradictory forces, and the artful exposure or concealment of inconsistencies. His book walks the same fine line as the details he discusses, outlining all sides of a debate that Ford sees as central to modern architecture, but his inordinate revelation of contrasting views muddies and obscures what might otherwise be a convincing position statement. In an effort at comprehensiveness, Ford undercuts the authority of his intriguing conclusion.

His selection of examples is adept at times, but often seems arbitrary, as if Ford had selected only buildings about which he had previously written instead of selecting them to support his argument. The dearth of canonical buildings is peculiar, but perhaps that is part of Ford’s argument. He takes issue with the way popular histories of modern architecture have been constructed, and this text (along with his previous books) serves as a corrective, refocusing attention on the making of buildings and how their construction can underline or complicate architectural ideas. For Ford, the independence of building parts is a pragmatic but also poetic solution to the modernist dilemma of form and function; architecture may be autonomous, but only because its parts do different things than paintings or novels or three piece suits. This definition of architectural autonomy – that its parts act independently based on their disparate purposes – is very different from that espoused by other theorists, whose disciplinary territorialism leads to un-collegial isolation.

Paradoxically, reading this book led me to reflect not on architectural details, but details in other disciplines, in particular fashion and literature. There are many analogs to Ford’s “autonomous” architectural details, one of the most obvious being the penchant in menswear for unexpected textures, patterns or colors in things like socks and pocket squares. In literature, similarly surprising details have instead been called “adventitious,” seemingly based on forces contrary or tangential to a narrative; Ernest Hemingway, for example, used these unexpected specifics to alter and ultimately amplify the power of his clean, straightforward descriptions.

Ford’s argument is similar, that buildings are flat and soulless without exceptions to prove the rule. The richness engendered by an intricate Alvar Aalto handrail or Carlo Scarpa structural connection is undeniable, and Ford does an admirable job outlining the reasons for the appeal of such subversive and unexpected componentry. This book is a worthwhile read for advanced students, practitioners, and anyone interested in philosophies of architectural assembly.

Princeton Architectural Press, 2011

Ultimate Mixtape #3: 20 Songs from 2011

Posted: 10 December 2011 Filed under: Music, Music Videos 2 CommentsLike I’ve done the last two years, here are some under-informed ramblings about my favorite tracks from the past calendar year. Feel free to ignore them.

*************************************************************************************************************

“The Wilhelm Scream” // James Blake

Blake started the year off right with his self-titled debut full length. And by right I mean correct for the winter months in the northern climate where I reside. Blake’s fusion of lounge singer vocals and dubstep low end felt transcendent during a gray February, but once summer rolled around it quickly left my rotation.

“Lotus Flower” // Radiohead

Most of The King of Limbs is a major downer, but “Lotus Flower” is almost danceable. See Thom Yorke in the video, for example.

“New Beat” // Toro y Moi

First of all, let’s get something out of the way: I hate Ariel Pink. I therefore wasn’t predisposed to loving Toro y Moi’s abrupt turn from atmospheric, Dilla-esque beatmaking to sun-drenched beach pop. But what has always differentiated Toro’s tracks from his peers is their messy humanity, and that characteristic is retained here despite the spit-shined sparkle.

“Rano Pano” // Mogwai

Mogwai released their strongest album in years, Hardcore Will Never Die, But You Will, and they also assaulted my eardrums at Mr. Small’s Theatre outside Pittsburgh. It was a revelatory concert, and one that cemented this song in particular on my best-of list. The video sucks, but I’ll forgive it.

“Wicked Games” // The Weeknd

Two well-publicized mixtapes and a few Drake collaborations later, The Weeknd’s work feels more contrived than when I first heard it, but no less cathartic.

“Lofticries” // Purity Ring

Purity Ring seem to have emerged fully formed from the internet ether. Sure, they’re aping The Knife a little, but given that the siblings Dreijer aren’t making any music of late this will have to do. For me, it’s more than satisfying.

“Ice Cream (feat. Matias Aguayo)” & “My Machines (feat. Gary Numan)” // Battles

Battles are at their most madcap and wonderful on Gloss Drop, and these two singles typify their post-Tyondai Braxton approach: hired vocal guns. I saw two excellent Battles sets this year, one at a festival and one in a small Cleveland venue, both of which augmented their live instrumental assault with large, expensive-looking video screens featuring the aforementioned guns, to dramatic effect.

“Putting The Dog To Sleep” // The Antlers

The Antlers provided the soundtrack for my sad bastard moments this year, and this track is the saddest of all. I’m not that into Hospice, their more critically lauded 2010 album, mostly because its themes of cancer and death and hospitals aren’t as universal as those explored on Burst Apart. The album strikes a deft balance between electronic and analog, along with specific and universal, and the results are profoundly affecting. “Put your trust in me / I’m not gonna die alone… I don’t think so…”

“Jaguar” // The Dirtbombs

A garage rock band covering Detroit techno? I’m in. Unfortunately, the rest of Party Store doesn’t hit quite as hard as this track for me. Great concept, above average execution.

“The Vision (feat. Jessie Ware)” // Joker

If he can make pop songs as convincing as this one, who cares if Joker has (arguably) turned his back on his dubstep roots? I predict he’ll be producing Beyonce and Rihanna before we know it.

“Are You Can You Were You? (Felt)” // Shabazz Palaces

Shabazz Palaces make what once upon a time would have been referred to as “abstract” hip hop, but these days are put in the “blunted” category along with Dilla and Madlib. On one level, the comparison is flattering, but the Stones Throw sample crowd has never produced anything this organic. The balance of electronic and analog is what makes this music sound so fresh and so clean.

“Banana Ripple” // Junior Boys

This is an excellent dance track from one of my favorite artists. It unexpectedly turns into something transcendent and trance-inducing after the 6:45 mark. Bit heavy on the treble though, boys. It’s tough to really crank it up.

“Please Turn” // Little Dragon

A number of Scandinavian bands ruled my airwaves this year. Particularly The Radio Dept. – who would have shown up on this list if their album hadn’t come out during 2010 – but also I Break Horses, Iceage, and Little Dragon. LD’s best track combines a great vocal performance from Yumiki Nagano, their signature electronic melodies, and an incessant foot-tapping beat.

“Otis (feat. Otis Redding)” // Jay-Z & Kanye West

A lot of critics wrote off Watch the Throne because it flouted the Roc brothers’ celebrity and conspicuous consumption. I say, there’s nothing we need more after three years of recession than a little fun. If Hova and Yeezy spend a little money bringing it to us, I say it’s a wash.

“We Bros” // Wu Lyf

I’ll admit it. I have no idea what this guy is sing-saying. He might as well be speaking Danish (this band isn’t Danish by the way), but I love this unintelligible but sunny reflection on brotherhood and solidarity nonetheless. The atmosphere of their album Go Tell Fire On The Mountain is what gets me, I can always feel the space its songs were recorded in, which is refreshing. And that organ!

“Ohio” // Justice

I really want to love Audio, Video, Disco, but I don’t. Most of its tracks are short on melody and just too short. There are blissful moments on the album, particularly the 1:00 mark of “On & On,” but Justice never lets them breathe. The burping synth breakdown here is utilized effectively, unlike similar cues on this new album. Also… this song is not about Ohio.

“All The Same” // Real Estate

Lackadaisical. Irreverent. Profound? [Note: This live version feels a bit rushed compared to what they put on record, but it highlights the chemistry these guys have on stage]

“Surgeon” & “Year of the Tiger” // St. Vincent

I could have chosen nearly any two tracks from St. Vincent’s excellent new album Strange Mercy. It’s easily my album of the year, and contains no less than six that I think warrant inclusion on a list such as this. Boiling her band down to drums, bass, keys and the occasional embellishment, Annie Clark has put her vocals and guitar front and center. This approach better approximates the effect of her live act. The stories on Strange Mercy are also Clark’s best so far. “Surgeon” is probably the best song I’ve ever heard about a fit of depression and features a completely unexpected, honest-to-God funk solo near its end. “Year of the Tiger” is the most apropos selection on this list given that its narrative is about an wealthy executive on the run a la Bernie Madoff or Raj Rajaratnam. Sketched through micro-scale details (an ever-growing stack of mail, a suitcase of cash in the back of a stick shift) these stories are affecting in ways I typically associate with literature and film.

Appendix // Here are a few 2011 tracks I hadn’t yet heard when I initially made my list. They deserve recognition:

“Wildfire (feat. Little Dragon) // SBTRKT

“Generation” // Liturgy

“Thinking About You” // Frank Ocean

“Marvin’s Room” // Drake

Brutalism: The Word Itself and What We Mean When We Say It

Posted: 20 November 2011 Filed under: Architecture, Brutalism, Events, Lectures 10 CommentsRecord of a Pecha Kucha-style presentation at Architecture + (Kent State), Friday November 18th, 2011

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The word “Brutalism” has lost its meaning. At present, it equates to: large buildings, sometimes of concrete, constructed sometime between World War II and the end of the 1970s. The sheer number of projects this describes is staggering, and many of the architects responsible for them in fact despised the term. We need to relearn the story of this pervasive locution.

Once upon a time, Brutalism referred only to “The New Brutalism,” a snide phrase coined by Alison and Peter Smithson to describe their unbuilt project for a townhouse in the SoHo neighborhood of London. For the Smithsons, “New Brutalism” was initially interchangeable with what they called “the warehouse aesthetic,” which sought to capture the raw quality of materials. As Peter Smithson pointed out in a late interview:

“Brutalism is not concerned with the material as such but rather the quality of the material, that is with the question: what can it do? And by analogy: there is a way of handling gold in Brutalist manner and it does not mean rough and cheap, it means: what is its raw quality?” [Peter Smithson: Conversations with Students, Princeton Architectural Press, 2004]

This raw quality, the treatment of materials “as found,” came to define the aesthetic proclivities of the group seen here, composed of the Smithsons, photographer Nigel Henderson, and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi. Eventually this group formed a part of The Independent Group, which is credited with launching Pop Art. For them, Brutalism was not a style but something else, hence:

“Brutalism tries to face up to a mass-production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work. Up to now Brutalism has been discussed stylistically, whereas its essence is ethical.” [Alison & Peter Smithson, “The New Brutalism,” Architectural Design (April 1957)]

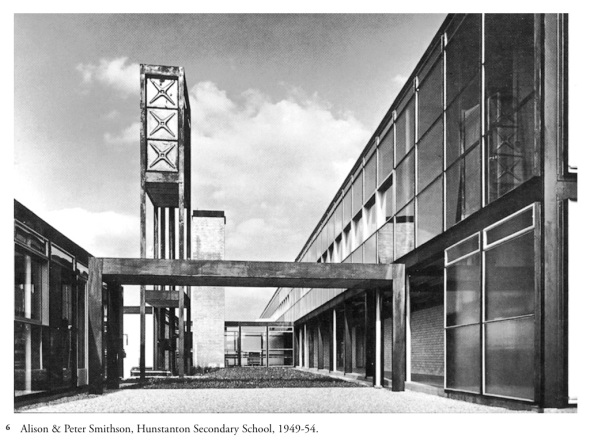

Immediately recognized as radical and transformative, “The New Brutalism,” was the subject of much debate. In fact, a series of think pieces had appeared in journals before the Smithsons managed to complete their first building, the Hunstanton Secondary School seen here.

One of brutalism’s strongest early supporters was historian and critic Reyner Banham. In 1955 he published an essay summarizing the defining characteristics of this new style as follows:

“1, Formal legibility of plan; 2, clear exhibition of structure, and 3, valuation of materials for their inherent qualities ‘as found.’”

Banham found this simple list inadequate, so he added:

“In the last resort what characterizes the New Brutalism in architecture […] is precisely its brutality, its je-m’en-foutisme, its bloody-mindedness.” [Banham, “The New Brutalism,” Architectural Review (December 1955)]

Banham later published what he purported to be the definitive statement on The New Brutalism, comprising an international selection of buildings. His contention was that the interplay of ethics and aesthetics defined production and reception of brutalism.

The trouble is, Banham excluded most of the buildings we now regard as brutalist. No Paul Rudolph, no Marcel Breuer, no Boston City Hall, and only one early project by Louis Kahn. And for the record, the Smithsons shunned Banham’s book, accusing him of co-opting their ideas to serve his own agenda.

Surely, the binary put forward by Banham is much too blunt and exclusionary. In order to rethink the word brutalism itself, it may be useful to return to the dictionary. Let’s look at the definitions of the parts in question. I’ve made a few redactions for the sake of brevity:

“brutal”

- savagely violent: a brutal murder

- punishingly hard or uncomfortable: the brutal winter wind

- without any attempt to disguise unpleasantness: the brutal honesty of his observations

“-ism”

- denoting an action or its result: baptism

- denoting a state or quality: barbarism

- denoting a system, principle or ideological movement: feminism

- denoting a basis for prejudice or discrimination: racism

- denoting a peculiarity in language: colloquialism

- denoting a pathological condition: alcoholism

[Oxford American Dictionary, 2007 Edition]

If we cut and paste a bit we might come up with something satisfactory:

“brutalism”: A state or quality of principled but pathological hardness or discomfort, without any attempt to disguise its unpleasantness.

A bit convoluted, but you get the point. Using this makeshift definition, the word itself might be reframed to describe a particular attitude about building, best described by Banham’s “bloody-mindedness.” Unlike the historically loaded word style, the idea of an attitude might effective at drawing together the diverse group of architectures to which we affix the word in question.

Universally recognizable by its severe, abstract geometries and the monolithic use of concrete, block and brick – this attitude called brutalism became a consensus approach to monumentalizing modern architecture.

If this story of Brutalism is indeed about consensus, our primary question should be: what made this uncompromising, imposing, and frankly quite impractical attitude so seductive?

The story of Paul Rudolph’s Art & Architecture building at Yale University might be instructive. Commissioned when Rudolph was appointed dean at the Yale School of Architecture, the completed building is overflowing with quotations and citations of the history of architecture.

Like Wright’s Larkin Administration Building, Rudolph wanted his work at Yale to have a sense of permanence, a built-in history, monumental enough to rival Roman ruins. In spite of his erudition, Rudolph’s building is most often remembered as the site of a mysterious arson.

The oft-cited myth is that a disgruntled architecture student, fed up with the building’s presence in his life, set fire to his desk in protest. True or not, this myth makes discussion of the building’s architectural merit or lack of merit extremely difficult. When we talk about Rudolph, we have to talk about the fire.

I’m tempted to cite Bernard Tschumi’s “Advertisements for Architecture,” in particular two sentiments expressed here, below the photographs:

On the left, “Architecture is defined by the actions it witnesses as much as by the enclosure of its walls.” And on the right, “Architecture only survives where it negates the form that society expects of it.” Through his actions, the arsonist responsible for Yale’s fire altered the narrative of Rudolph’s building and of brutalism in general, but might the story someday change?

While no mysterious event clouds our view of the Hunstanton School, the overwhelming personal narrative constructed by Alison + Peter Smithson certainly does. Known for talking big and building little, the Smithsons were never as successful as their books would have you believe.

Their largest project, Robin Hood Gardens council housing in London, is one of the worst failures of urban renewal during the brutalist moment. Its foundering hurt their reputations, and larger commissions never came their way. Unlike Rudolph, however, the Smithsons regained their stature by changing their attitude. Their work in the 1970s traced a shift away from the unhomely airs of brutalism toward a sophisticated engagement with Postmodernism, and a more open embrace of history.

The story of brutalism reminds us that once upon a time, there was disciplinary consensus. In retrospect, this consensus appears a peculiar convergence between ethics and aesthetics, during which truth in materials and the question of monumentality dominated the discipline no matter one’s ideological bent, a time when do-gooders and designers held certain goals in common. Successful or not, the results of this peculiar convergence are all around us, reminders that we could all use an attitude adjustment.

Publication Notes

Posted: 11 June 2011 Filed under: Architecture Leave a commentA few quick announcements regarding publication through other outlets:

I have a short piece concerning Farshid Moussavi’s design for the Museum of Contemporary Art (MoCA) Cleveland in the Ohio State student architecture journal One:Twelve. Using MoCA as a starting point, I scrutinize architecture’s still naive engagement with film through “virtual tours.” Edited, designed and partly written by graduate and undergraduate students at the Knowlton School of Architecture, One:Twelve publishes once a quarter, and they have just completed their first academic year. You can read my contribution here, or view a PDF of the issue in which it appears here.

Another (very short) piece of mine on the work of Bjarke Ingels Group will be published in the inaugural CLOG pamphlet, organized and edited by a group of young New York architects. From the CLOG call for submissions:

Forums such as social media, online press, blogs and tweets have drastically increased the rate at which architectural imagery is distributed and consumed today. While an unprecedented range of work is now accessible to the public, the constantly updating avalanche of architectural imagery has reduced any single project’s lifespan with Architecture’s collective consciousness to a week, an afternoon, a single post… an endless churning architecture du jour. CLOG deliberately slows down this flow of information, providing a place to reflect, discuss, and take aim.

The first pamphlet will focus on BIG, and will have contributions from a motley crew of young critics and academics. An outgrowth from a previous blog post on the Mountain Dwellings, my piece focuses on the use of narrative diagrams in BIG’s work. I will post a link here when one becomes available.

(UPDATE: CLOG now has a web presence at www.clog-online.com and the Storefront for Art & Architecture will be hosting a launch party for their first issue on October 7th. If you are in New York be sure to check it out.)

Also, I have had a tumblr.com account for some time now, focusing on the loose aggregation of international building styles collectively referred to as Brutalism. I have pored over the collections of my local libraries, seeking out and scanning compelling images and drawings from such architects as Marcel Breuer, Paul Rudolph, Kevin Roche, and Kenzo Tange, among many others. This “blog junior” can be found at (pardon my Tumblr patois): fuckyeahbrutalism.tumblr.com